Case Study: Media Ethic Analysis of John Naughton’s AI Cheating Article

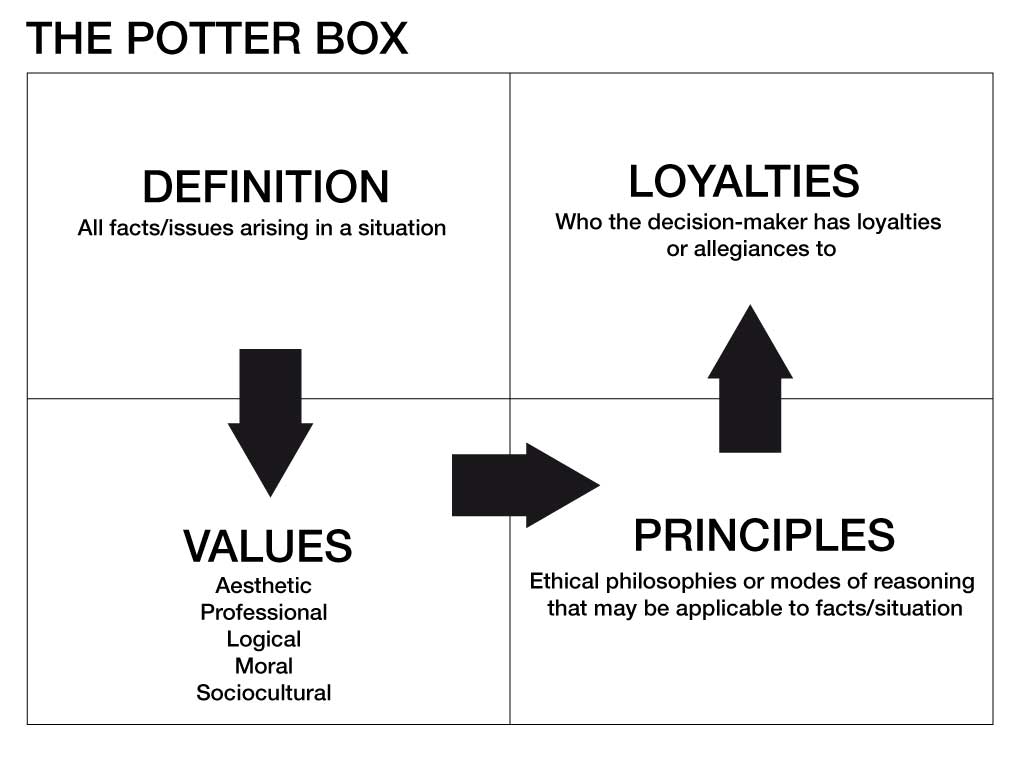

On August 24, 2024, the professor of the public understanding of technology at the Open University John Naughton published an article “AI cheating is overwhelming the education system – but teachers shouldn’t despair” on The Guardian News website (Naughton 2024). In the comment section of this article, we see both agreement and disagreement. For instance, A user named “convent” agrees with the authors’ viewpoint on the value of human-written paper, while another user named “JohnHLister” criticized the authors’ view as Luddite. In this case study, we aim to analyze the media ethics of John Naughton’s article using Potter Box developed by Ralph B. Potter (Christians et al. 2020, 4). The rest of the case study is structured as follows. First, we define the four matrices of Potter Box as referenced in Figure 1 (Definition, Values, Principles and Loyalties). Second, we extract the definitions and values in the AI cheating case defined by the article, then validate the facts in definitions, as well as comparing the values from different parties. Third, we choose the Judeo-Christian’s principle of agape and loyalties of the public. Finally, based on the ethical principles and loyalties of our choice, we analyze John Naughton’s claims and analyze if the claims match ethical standards.

The Potter Box contains four dimensions: Definition, Values, Principles and Loyalties. According to Clifford G. Christians, Potter Box is used from one quadrant to the next, and the action guide is determined at the final stage (2020, 5). We first give definitions of the situation, citing enough details and facts provided by the author related to the article’s main argument. Second, we determine the values beneath the facts, citing the values that might be important. We then choose the most credible ethical principles based on the social environment of the target audience at quadrant 3, and loyalty at quadrant 4 based on the Guardian’s core purpose and values.

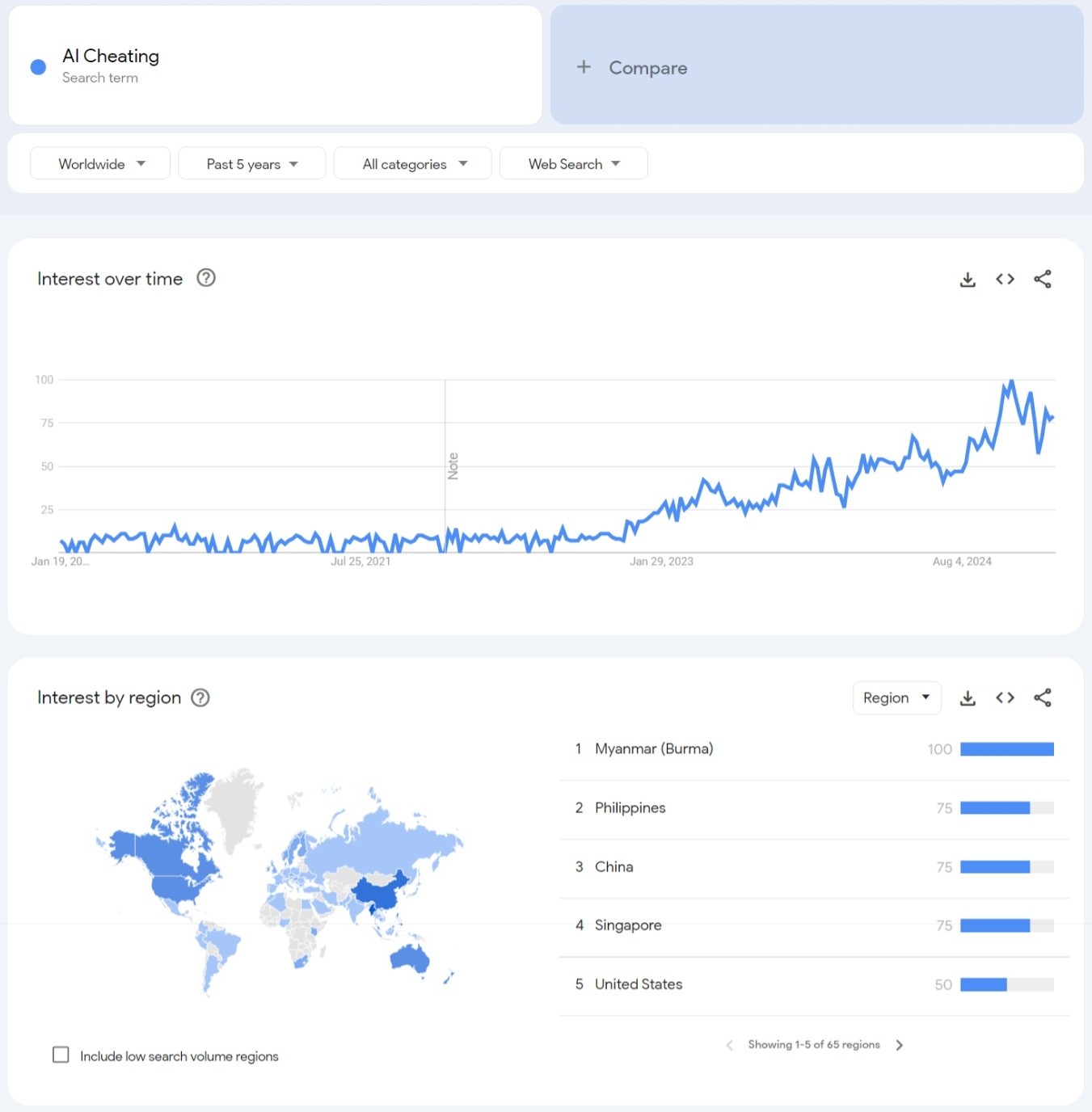

John Naughton’s article discusses the challenges of large language model’s harm on education system, especially in humanities disciplines. The core challenge is the absurdism AI tools created where teachers struggle to distinguish between student and AI-generated works. In the definition quadrant, we identify six facts John mentioned. 1. AI cheating is getting popular. 2. A university professor states that the AI usage makes teachers struggle when grading. 3. OpenAI intentionally hides the tool used for AI essay detection, and this decision infuriates academia that expect a technical product to fix the “cheating” problem. 4. Researchers have concluded that software detecting output of AI systems accurately is not possible now. 5. AI is “cultural technologies” for human augmentation not replacement. 6. Universities are not noticing the threat of technologies in the education system. Among the six definitions, fact 2, and 5 have appropriate hyperlinks to the related articles or publications. For instance, fact 5 is based on a talk by a researcher at Harvard University, Alison Gopnik explains AI as a tool to summary and transmission of human knowledge in her talk between 00:00:45 to 00:03:00 (2024). Peer-reviewed articles validate the challenges in AI detection and watermarking systems discussed in fact four, but John does not provide a reputable source. For example, Elkhatat’s research in 2023 confirms John’s argument that the detection tools shows inaccurate results (2023, 14). The popularity of the AI cheating topic in fact 1 is confirmed by Google (n.d.), as shown in Figure 2. Fact 1 and 6 cannot be validated and the facts are not expressed neutrally. As of fact 1, The article mentions “This refusal [from OpenAI] infuriates those sectors of academia (2024).” John does not state who expressed the infuriation from which sectors of academia. As of fact six, John also did not cite the source of information, as the article only mentions the opinion from “every UK vice-chancellor or senior university administrator I [the author] met” instead of a specific person from the system. As a result, we do not have enough evidence to agree with these facts or definitions. In summary, the definitions in the article can mostly be validated. However, we find two facts not trustworthy, causing less reputation to John’s argument.

In the second stage of Potter Box, we identified three major values in this short article. The three parties involved in the situation are OpenAI, students using AI tools and educators who are grading students. The values in Potter Box motivate actions (Christians et al. 2020, 6). We summarize four values from the related parties. From OpenAI’s perspective, they attach to their commercial values. OpenAI sells their AI LLMs as subscription. Students in higher education is one of the largest customer groups for OpenAI. Releasing dedicated tools for educators to detect AI usage will significantly decrease their revenue. There is also compassion for students. In the US and UK, students pay for their tuition fees in higher education. For students, their goal is to both practice their writing skills and get a degree. However, getting the degree has a higher priority because that may be directly related to their future jobs, or they depend on student loans. The third value is the educator’s value. For educators, writing as an intellectual activity helps students think and develop arguments. Writing with LLMs makes students shift writing from the process to the final product which is bad for their learning.

As Christians stated in the introduction to Potter Box, “there is no one theory can satisfactorily resolve all the questions and dilemmas in media ethics (Christians et al. 2020, 13).” We must choose the most proper theory for the audience and the parties mentioned in the article. In this case study, we choose Judeo-Christian’s principle of agape as the ethical principle. The Guardian newspaper is from the UK, we assume there is a considerable number of subscribers and readers in its country of origin. In the article John writes, John frequently quotes researchers and educators in the US for their opinions. The article is in the international version of The Guardian. We also assume a considerable number of target audiences located in the US. In both regions, Christian ethical standards are dominant. According to PRRI’s research in the US, at least 50% of people are Christians (2023). In the UK, 46.2% of the population report Christian (Office for National Statistics 2022). Because of this, we choose the agape as the ethical principle. Agape encourages acceptance of other people’s existence. Love does not estimate the rights and then determines one’s merits attention. John’s article explains the harms of using AI tools in higher education, which shows his caring for teachers for their good intentions to warn students about the dangers of AI cheating. He also shows his love for the students and the concern that students will not be able to improve themselves. To match with the ethical standards, John could improve the organization of his article and show more compassion for the students, as it overlooks the perspective of students who resort to AI cheating due to a lack of time and effort to fully engage in the learning process.

Because of the slight bias John presents in the values under agape, John’s loyalty does not fully match ethical standards. As a journalist, John Naughton has loyalty to the employer, themselves, and the public. John successfully demonstrates his loyalty to the employer, which is The Guardian and Open University. John has cited most of the sources in his article, demonstrating a commitment to journalistic integrity and accountability. This approach reflects loyalty to his employer, The Guardian, by upholding its reputation as a credible and reliable news outlet. This also shows loyalty to the public, ensuring they receive accurate and truthful information. He also demonstrates loyalty to the university by addressing the concerns of teachers regarding the issue of AI cheating. By speaking on behalf of the teachers, Naughton aligns his argument with the interests of his coworkers. At the end of the article, John criticized the universities’ administration, prioritizing his loyalty to the public over his loyalty to his employer. However, John falls short in terms of the loyalty to himself, as he brings careerism into his article by using biased phrases such as “infuriate” without proper reference. He also failed to show compassion for the values other than the teachers, who act out of his own self-interest.

Overall, John fairly presents the definitions and values of different parties, and it meets with the basic ethical standards. However, the article would benefit from greater neutrality and balanced representation of all stakeholders. If John provides a more comprehensive demonstration of compassion and fairness to parties other than teachers, it will align fully with the ethical standards it aims to uphold.